By Dr. Tim Orr

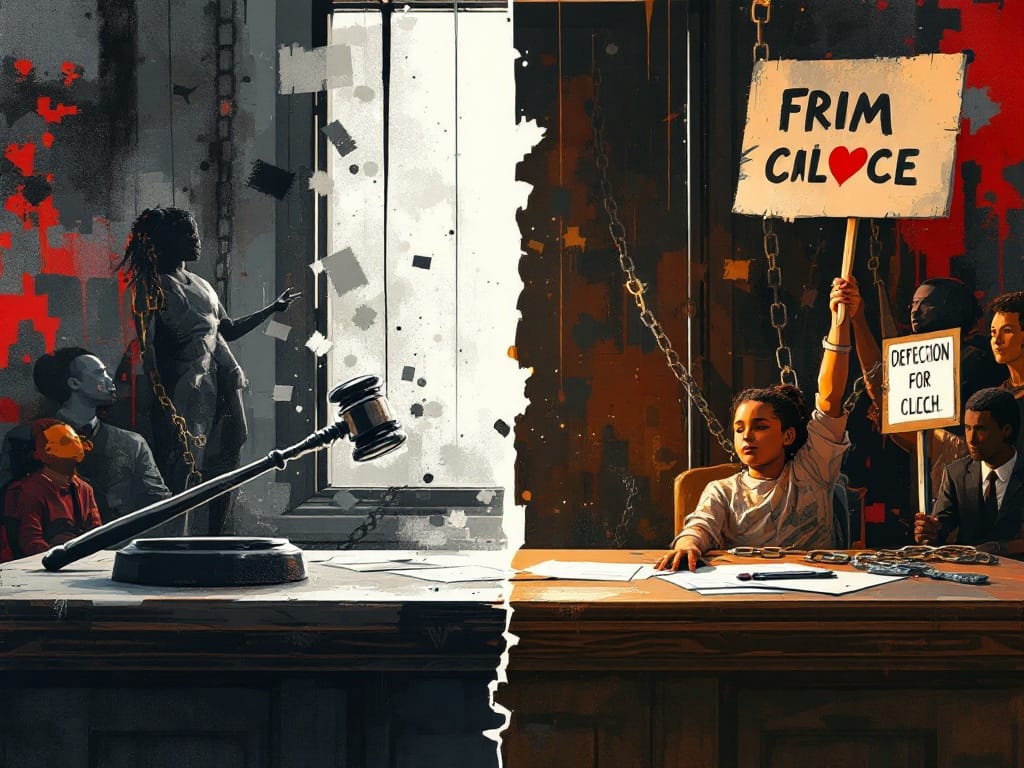

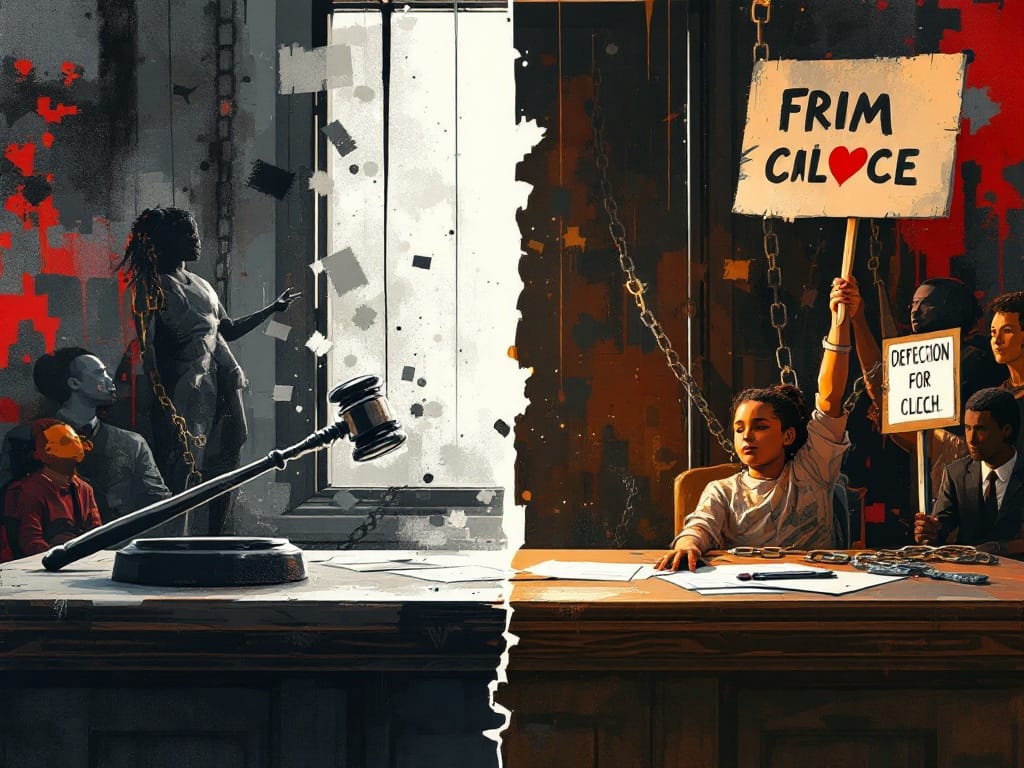

Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson recently equated Tennessee’s law prohibiting irreversible medical interventions on children to the anti-miscegenation laws of the Jim Crow era. Such a comparison reveals a profound misunderstanding of history, science, and ethics. It not only trivializes the historical atrocities of racial oppression but also fails to grapple with the grave consequences of medical interventions aimed at altering a child’s biological sex.

By conflating the two, Justice Jackson undermines the legacy of civil rights and obscures the critical moral and medical issues at stake, particularly the irreversible harms inflicted on minors under the guise of "gender-affirming care."

The Distorted Comparison of Race and Gender

Anti-miscegenation laws, overturned by the Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia (1967), were explicit tools of systemic racism. These laws aimed to uphold racial purity and segregation, criminalizing interracial relationships and dehumanizing people based on immutable traits such as skin color.

Tennessee’s law, by contrast, is not rooted in prejudice or an effort to deny anyone dignity. It focuses on protecting children—who are incapable of providing informed consent—from medical procedures that are not only irreversible but also experimental. These include puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgeries that permanently alter or remove healthy body parts. Such interventions have far-reaching consequences, often leaving individuals physically and emotionally scarred.

Equating laws designed to protect minors with laws that perpetuate systemic racism is both historically inaccurate and ethically irresponsible. It reduces a complex medical and ethical debate to a false narrative of discrimination.

Irreversible Interventions and the Long-Term Harm to Children

The medical interventions targeted by Tennessee’s law are neither benign nor reversible. They involve profound changes to a child’s body that carry lifelong consequences. Consider the case of removing the ovaries of a 12-year-old girl, a procedure sometimes performed as part of gender-affirming surgeries. This act is not merely a symbolic affirmation of identity—it causes immediate and irreversible menopause.

Menopause at such a young age introduces a host of complications, including hormonal imbalances, osteoporosis, cardiovascular issues, and infertility. The child is thrust into a state of biological dysfunction, requiring lifelong medical intervention to manage the consequences of the initial procedure. These are not minor or speculative side effects—they are the inevitable results of irreversible surgeries performed on minors.

Similar harms occur with other interventions. Puberty blockers, often described as a "pause button," can disrupt bone density development and compromise future fertility. Cross-sex hormones introduce risks such as blood clots, heart disease, and permanent changes to secondary sexual characteristics. These treatments fundamentally alter a child’s natural development, often leaving them dependent on medical interventions for life.

In this context, Tennessee’s law seeks to protect children from making decisions—or having decisions made for them—that they are not cognitively or emotionally equipped to understand. Laws like these reflect a growing recognition, even in progressive countries such as Sweden and Finland, that these interventions carry significant risks and should not be pursued lightly.

The Ethical Crisis of Gender Ideology in Medicine

Justice Jackson’s comparison ignores the growing body of evidence highlighting the dangers of gender-affirming medical interventions for minors. Puberty blockers and surgeries are often performed without sufficient understanding of their long-term effects, and detransitioners—those who regret their medical transitions—have become vocal about the irreversible harm they suffered.

For example, Keira Bell, a detransitioner from the United Kingdom, underwent a medical transition as a teenager and later expressed deep regret for the permanent changes to her body, including the loss of her fertility. Bell’s case prompted a judicial review in the UK, leading to stricter guidelines around prescribing puberty blockers to minors. Stories like hers are increasingly common, yet they are often dismissed in the rush to affirm gender identities without scrutiny.

Justice Jackson’s analogy trivializes these profound ethical concerns. By framing opposition to these procedures as akin to racism, she dismisses the legitimate fears of parents, medical professionals, and detransitioners who are sounding the alarm about the long-term consequences of these interventions.

The Exploitation of Civil Rights Language

The civil rights movement was rooted in the recognition of universal human dignity. It sought to dismantle laws that dehumanized individuals based on immutable characteristics. By invoking this legacy to defend experimental medical procedures on children, Justice Jackson appropriates the moral weight of civil rights to advance an ideology that is deeply contested and scientifically dubious.

This tactic undermines the historical significance of the civil rights movement and silences debate. Framing opposition to child medical transitions as bigotry shuts down critical conversations about ethics, science, and the rights of parents and children. It weaponizes the language of civil rights to delegitimize dissent, turning a complex medical and ethical issue into a simplistic narrative of oppression.

The Judiciary’s Responsibility to Protect the Vulnerable

The judiciary has a moral and constitutional duty to protect society's most vulnerable members. Children, who lack the cognitive maturity to fully understand the consequences of life-altering decisions, are among the most vulnerable. Neuroscience confirms that the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for decision-making and impulse control—does not fully develop until the mid-20s. This makes minors particularly susceptible to ideological and social pressures.

Tennessee’s law reflects this understanding. It does not deny adults the right to pursue medical transition; it simply places limits on irreversible procedures for minors. Similar safeguards exist in other areas of the law: minors cannot purchase alcohol, enter into contracts, or join the military. These restrictions are not discriminatory; they are protective measures designed to ensure that children are not exploited or harmed.

Anti-miscegenation laws, by contrast, were designed to oppress. They denied adults their fundamental rights and reinforced systemic injustice. To compare these two legal frameworks is not only misleading but deeply offensive to those who fought against racial oppression.

Conclusion: Protecting Children Is Not Oppression

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s comparison of Tennessee’s law to anti-miscegenation statutes is historically inaccurate and morally irresponsible. By equating child protection laws with racist oppression, she trivializes the profound harms inflicted by medical interventions on minors and misrepresents the intent of the law.

The fight to protect children from irreversible harm is not an act of discrimination—it is an act of justice. The conversation about gender ideology, medical ethics, and children’s rights deserves thoughtful and nuanced engagement, not shallow analogies that distort history and obscure the real issues at stake.

Protecting a 12-year-old girl from losing her ovaries and entering premature menopause is not oppression—it is compassion. Safeguarding minors from irreversible medical procedures is not bigotry—it is responsibility. Justice demands clarity, not conflation, and the children affected by these debates deserve nothing less.

Tim Orr is a scholar of Islam, Evangelical minister, conference speaker, and interfaith consultant with over 30 years of experience in cross-cultural ministry. He holds six degrees, including a master’s in Islamic studies from the Islamic College in London. Tim taught Religious Studies for 15 years at Indiana University Columbus and is now a Congregations and Polarization Project research associate at the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture at Indiana University Indianapolis. He has spoken at universities, including Oxford University, Imperial College London, the University of Tehran, Islamic College London, and mosques throughout the U.K. His research focuses on American Evangelicalism, Islamic antisemitism, and Islamic feminism, and he has published widely, including articles in Islamic peer-reviewed journals and three books.

Sign up for Dr. Tim Orr's Blog

Dr. Tim Orr isn't just your average academic—he's a passionate advocate for interreligious dialogue, a seasoned academic, and an ordained Evangelical minister with a unique vision.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.