By Dr. Tim Orr

When I first read Hebrews 9 years ago, I was struck by its radical message: a superior covenant, a high priest who enters the true Holy of Holies, and a sacrifice that brings eternal redemption. It’s a passage that challenges the idea of religion as mere rule-following and instead introduces us to a once-for-all sacrifice that changes everything. However, as I studied Islam more deeply, I began to see how differently it approaches the concept of atonement and divine-human interaction. With its emphasis on legal obedience and personal merit, Islam offers a striking contrast to the theology of Hebrews 9. Let’s explore these differences together, diving deeper into how they shape the lived experiences of Christians and Muslims.

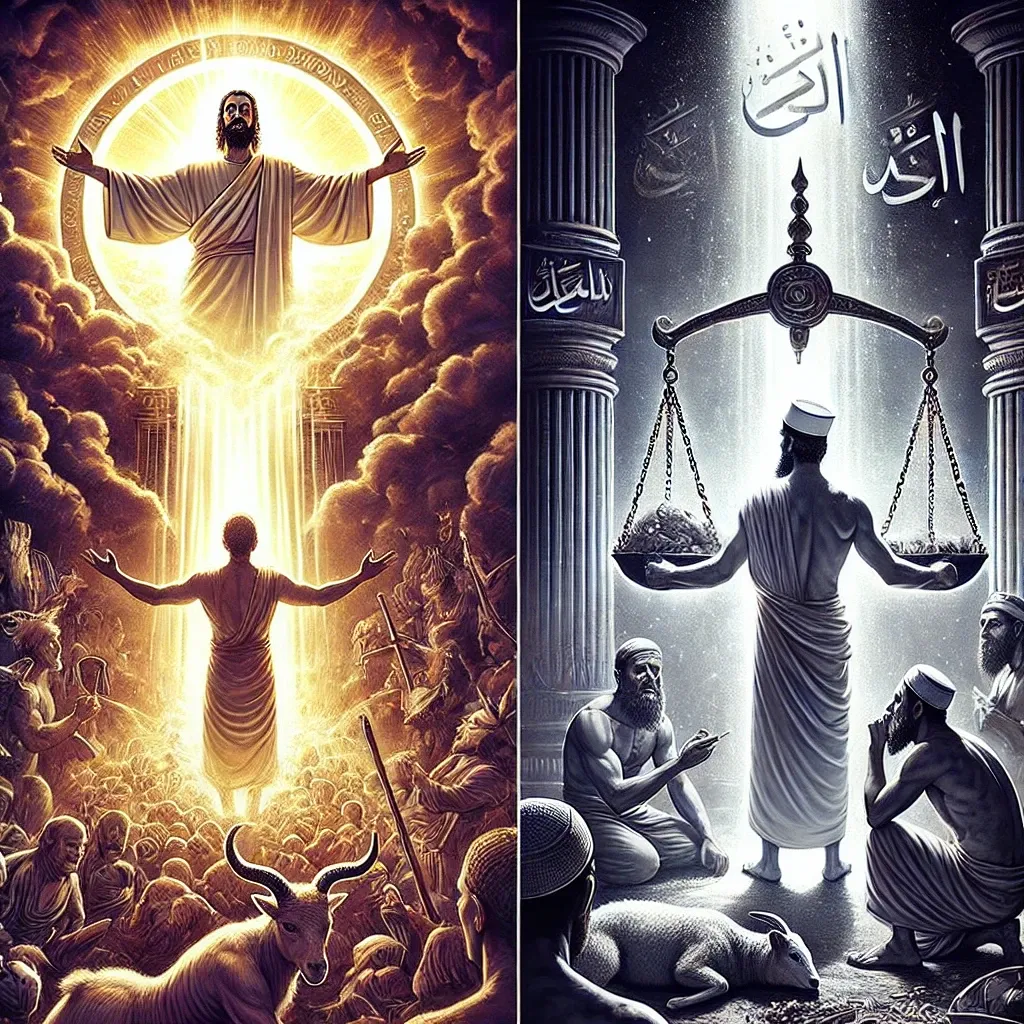

Sacrifice and Atonement: Christ’s Blood vs. Human Effort

The theme of sacrifice is central to Hebrews 9. The chapter describes how, under the Old Covenant, priests had to offer animal sacrifices regularly to atone for sins. But Hebrews 9:12 declares something revolutionary:

“He entered once for all into the holy places, not by means of the blood of goats and calves but by means of his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption.” (ESV)

This passage teaches that Jesus’ sacrifice is final and complete. Unlike the repeated sacrifices of the Levitical system, which only temporarily covered sins, Christ’s atonement removes sin permanently. His blood accomplishes what no human effort or religious ritual could achieve. The theological significance of this cannot be overstated: without the shedding of blood, there is no forgiveness of sins (Hebrews 9:22). The Old Testament system required continuous offerings, pointing to the ultimate, once-for-all sacrifice of Christ.

The notion of atonement in Christianity differs significantly from that of Islam. The Qur’an explicitly rejects the idea that one person can take on the sins of another:

“And no bearer of burdens will bear the burden of another.” (Qur’an 6:164)

This means that, in Islam, each person is individually responsible for their sins. Forgiveness is granted based on repentance, prayer, and good deeds rather than a substitutionary sacrifice. While Islam recognizes the practice of animal sacrifice (Qurbani) during Eid al-Adha, this is symbolic and not for atonement in the Christian sense (Esposito, 2018). Instead, Muslims believe that forgiveness is ultimately at Allah’s discretion, leaving them without the assurance Hebrews 9 provides. Without a final atoning sacrifice, the burden remains on the individual to maintain righteousness before God.

The Role of the High Priest: Christ vs. No Intermediary

One of the key arguments in Hebrews 9 is that Jesus serves as the eternal high priest who enters the heavenly sanctuary on behalf of humanity. Hebrews 9:24 states:

“For Christ has entered, not into holy places made with hands, which are copies of the true things, but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God on our behalf.” (ESV)

Under the Old Covenant, the high priest would enter the Holy of Holies once a year to offer a blood sacrifice for the people’s sins (Leviticus 16). But now, Jesus enters heaven's true Holy of Holies, directly interceding for us. This act of divine mediation provides a way for believers to access God with full assurance, knowing that Christ is their advocate (1 John 2:1).

Islam, however, does not have a high priestly figure. Muslims believe that they must approach Allah directly through their own prayers and deeds. The Qur’an states:

“And when My servants ask you concerning Me, indeed I am near. I respond to the invocation of the supplicant when he calls upon Me.” (Qur’an 2:186)

This verse emphasizes direct access to Allah, with no need for an intercessor. While this might seem empowering, it also means that the weight of religious obligation falls entirely on the individual. There is no mediator who pleads on behalf of sinners, leaving Muslims in a state of uncertainty about their standing before God (Haleem, 2005). In contrast, Hebrews 9 teaches that Jesus, as our high priest, continually intercedes for us, securing our access to God not through our merit but through His work.

Without a high priest in Islam, the responsibility for atonement and salvation is placed on the individual. This creates a vastly different understanding of divine justice and mercy. Hebrews 9 presents Jesus as both the sacrifice and the priest, fulfilling both roles to remove human effort from the equation and replace it with God’s grace.

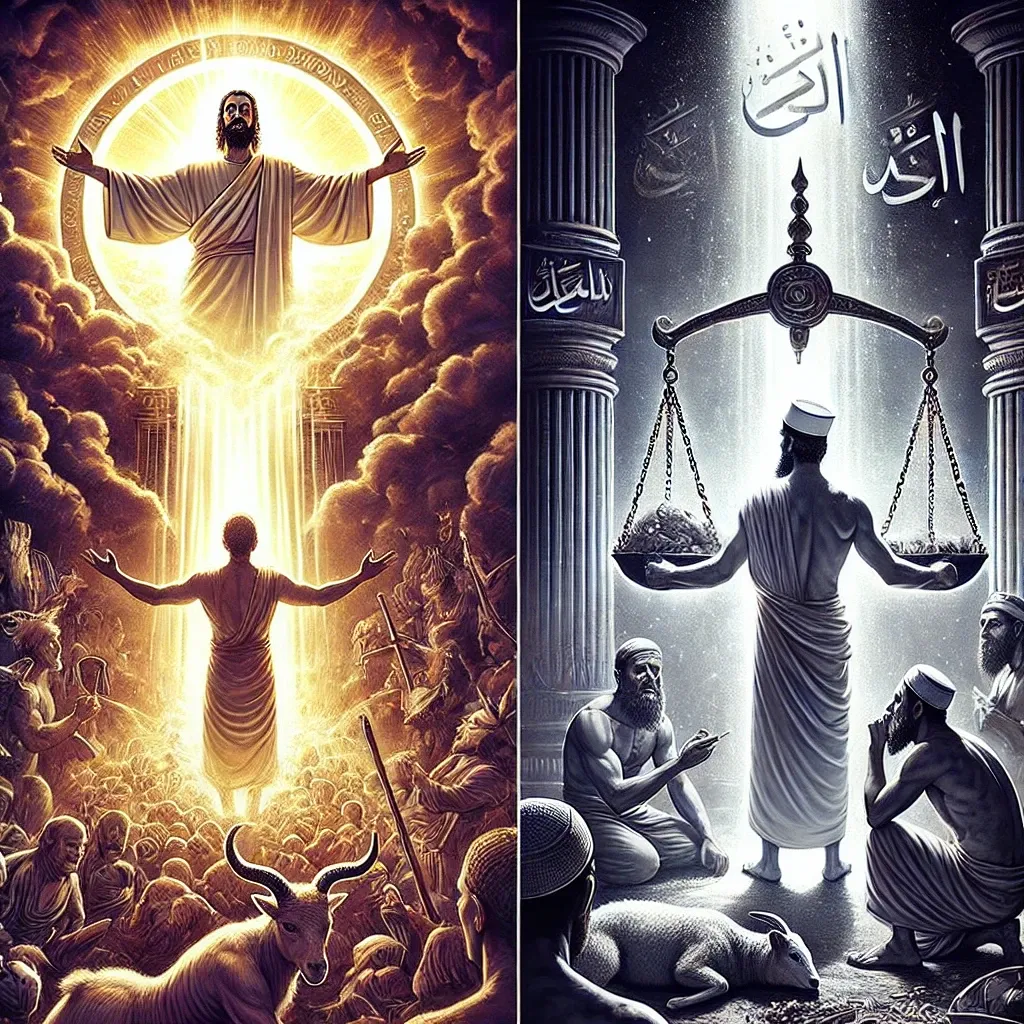

The Finality of Christ’s Sacrifice vs. Ongoing Human Effort

A key message of Hebrews 9 is that Christ’s work is once and for all. Hebrews 9:26 declares:

“But as it is, he has appeared once for all at the end of the ages to put away sin by the sacrifice of himself.” (ESV)

This statement carries profound theological weight. It means that the entire burden of sin has been dealt with in a single, decisive act. Unlike the Old Testament system, which required repeated sacrifices year after year, Jesus’ sacrifice was sufficient for all time. The phrase “once for all” signifies finality, completeness, and absolute sufficiency. Nothing more is required to cleanse humanity from sin. The believer’s salvation is secure—not because of personal righteousness but because of Christ’s perfect, finished work.

In contrast, Islam requires ongoing human effort to achieve divine favor. The Qur’an teaches that each person will be judged by the weight of their deeds:

“Then those whose scales are heavy [with good deeds]—it is they who will be successful. But those whose scales are light—those are the ones who have lost their souls, [being] in Hell, abiding eternally.” (Qur’an 23:102-103)

This passage illustrates the Islamic concept of salvation, which is based on balancing good and bad deeds. Even Muhammad himself reportedly expressed uncertainty about his final destiny:

“By Allah, even though I am the Apostle of Allah, yet I do not know what Allah will do to me.” (Sahih al-Bukhari 5:266)

This uncertainty contrasts with the confidence Christians have in Christ’s finished work. The assurance of salvation in Hebrews 9 removes the anxiety of never knowing whether one has done enough. In Islam, even the most devout believer must continue striving, hoping their efforts will be enough. Hebrews 9 provides a starkly different hope—one that is not dependent on human effort but fully secured in Christ.

Conclusion: Temporary vs. Eternal Redemption

Hebrews 9 presents a revolutionary contrast between temporary, repeated sacrifices and one eternal act of redemption. Christianity teaches that Christ’s perfect sacrifice secures salvation, while Islam emphasizes ongoing efforts, uncertainty, and individual responsibility for one’s sins (Esposito, 2018).

This raises a fundamental question: Do we want to trust in our own works or in a Savior who has already done the work for us? Hebrews 9 invites us into the reality of complete atonement, secured through Jesus, where we can confidently approach God not by our merit but by His grace.

And that is the greatest news of all.

References

Esposito, J. L. (2018). Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford University Press.

Haleem, M. A. S. (2005). The Qur’an: A New Translation. Oxford University Press.

Nasr, S. H. (2015). The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary. HarperOne.

Sahih al-Bukhari 5:266.

Dr. Tim Orr works full-time at Crescent Project as the assistant director of the internship program and area coordinator and is very active in UK outreach. He is a scholar of Islam, Evangelical minister, conference speaker, and interfaith consultant with over 30 years of experience in cross-cultural ministry. He holds six degrees, including a master’s in Islamic studies from the Islamic College in London. He is a Congregations and Polarization Project research associate at the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture at Indiana University Indianapolis. His research focuses on American Evangelicalism, Islamic antisemitism, and Islamic feminism. He has spoken at prestigious universities and mosques, including Oxford University, Imperial College London, and the University of Tehran. He has published widely, including articles in Islamic peer-reviewed journals, and has written four books.