By Dr. Tim Orr

For the past five years, I’ve traveled to London twice a year, staying in predominantly Muslim neighborhoods. These trips have become a cherished rhythm—opportunities to connect with people whose warmth, hospitality, and vibrant culture continually inspire me. Over the past decade of engaging in interfaith dialogue, I’ve deeply appreciated these moments of connection. Yet, I’ve also learned to notice when something isn’t right. During my last couple of trips, in the shadow of the October 7 attacks, I witnessed something that left me deeply unsettled: not just the presence of extremist rhetoric but its spread into the moderate circles I’ve long admired.

At places like Speaker’s Corner, where passionate debates are the norm, I noticed a sharper edge to the conversations—a shift in tone that blurred the lines between moderates and extremists. In neighborhoods where I’ve often found dialogue and coexistence, I saw individuals I once knew as voices of reason echoing narratives that glorified violence or demonized entire groups. It was as if the collective trauma of global events revealed to me how widespread Islamic antisemitism is.

This experience led me to wrestle with a critical question: What factors contribute to this radicalization? Is it the unrelenting cycle of global conflicts, with their devastating images and narratives that inflame pain and anger? Is it the isolation some feel in the West, caught between cultures and struggling to reconcile identity? Or perhaps the ever-present power of social media, where extremist voices manipulate outrage and amplify division? These questions linger in my mind, and the answers are complex. However, one thing is clear: understanding these factors is essential to bridging divides and fostering a path back to peace. Let me take you deeper into what I saw and learned through this journey. In this blog, I will outline only one of many possible reasons.

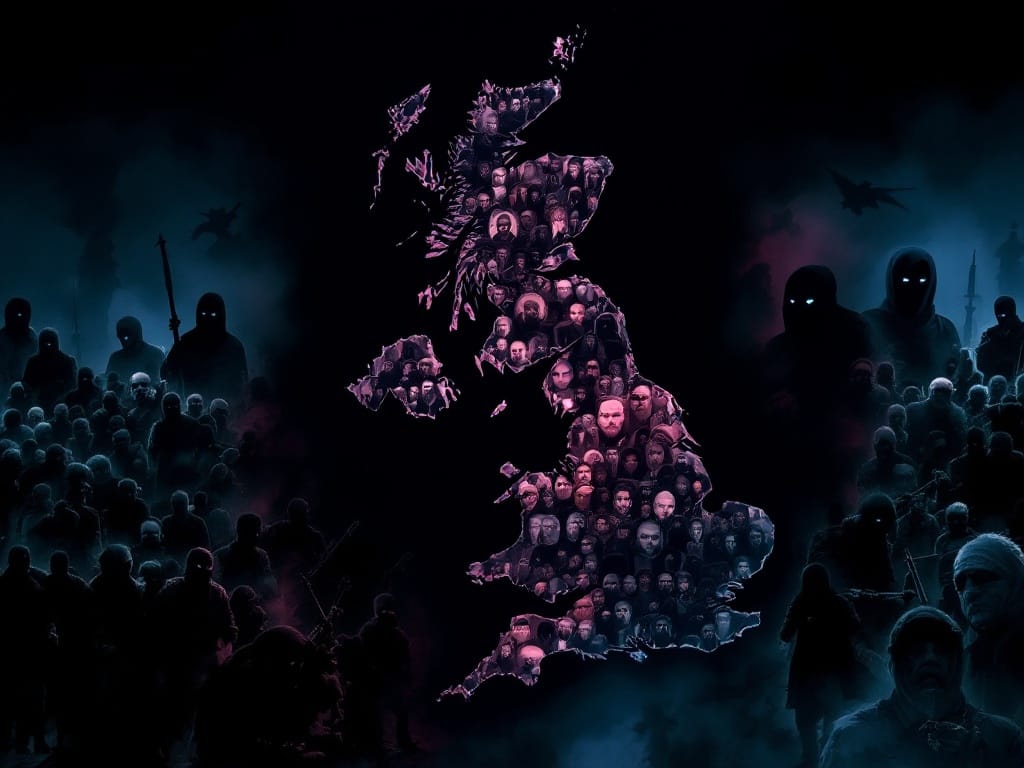

The United Kingdom has a proud history of offering sanctuary to those fleeing persecution. For decades, it has stood as a beacon of democracy and human rights, where individuals can escape injustice and rebuild their lives. However, this commitment to protecting the vulnerable has occasionally been exploited. Among the asylum seekers were Islamist leaders who came not just to seek safety but to use the freedoms Britain provided to spread radical ideologies. While the intention to offer refuge was rooted in noble ideals, the long-term consequences have been profound—and not always positive.

By looking at the policies that shaped these decisions, the leaders who took advantage of them, and the lasting impacts on British society, we can understand how a story of hospitality became one of unintended consequences.

Why Britain Opened Its Doors

At its core, Britain’s asylum policies reflect the country’s deeply held belief in protecting human rights. After World War II, the UK helped draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and became one of the first signatories of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). These frameworks promised the world that Britain would be a haven for those in danger.

In 1998, the Human Rights Act brought these principles into domestic law, strengthening protections for those seeking refuge. For many, these policies offered a lifeline. But they also created challenges for individuals linked to extremism. People like Abu Qatada were able to avoid deportation for years by arguing that they would face torture or unfair trials if sent back to their home countries (Casciani, 2014). The courts often sided with them, placing human rights above concerns about national security.

It wasn’t just legal principles at play. During the Cold War, Britain and its Western allies welcomed Islamist dissidents as a counterweight to secular authoritarian regimes in the Middle East. Figures opposing leaders like Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser or Syria’s Hafez al-Assad were granted sanctuary. At the time, this might have seemed like a strategic move. However, these decisions brought ideological battles from the Middle East into Britain’s backyard.

The Leaders Who Shaped Britain’s Extremist Landscape

The UK became home to several high-profile Islamist leaders who used their newfound freedom to build networks and spread their ideas. Their stories reveal just how complicated this issue became.

Abu Qatada: The Cleric Who Stayed Too Long

Abu Qatada arrived in the UK in 1993, claiming he was fleeing persecution in Jordan. To many, he was a scholar and a refugee. But soon, he was described as “Osama bin Laden’s ambassador in Europe.” His sermons called for violence against non-Muslims and encouraged jihad. Recordings of these speeches were even found in the homes of the 9/11 attackers (Phillips, 2006).

The UK government spent nearly two decades trying to deport Qatada. Every time, the courts blocked the move, citing fears that evidence obtained through torture might be used against him in Jordan. This drawn-out legal battle frustrated officials and the public alike. While he was eventually deported in 2013 after assurances from Jordan, his case symbolized the difficulties of balancing human rights with national security.

Omar Bakri Muhammad: The Father of British Jihadism

Omar Bakri Muhammad came to Britain in 1986 and became a polarizing figure. He initially joined Hizb ut-Tahrir, a global Islamist organization, but later founded al-Muhajiroun, a group that openly celebrated acts of terrorism. Under Bakri’s leadership, al-Muhajiroun became a breeding ground for extremism. Many of its members later joined terrorist organizations like al-Qaeda and ISIS (Wiktorowicz, 2005).

Even after fleeing to Lebanon in 2005, Bakri continued influencing his UK followers through online sermons. His teachings inspired countless individuals, contributing to the rise of homegrown extremism.

Anjem Choudary: The Media-Savvy Radical

Anjem Choudary, a disciple of Bakri, became the public face of British extremism. Unlike his predecessors, Choudary had a knack for using the media to amplify his message. He co-founded al-Muhajiroun and openly supported ISIS. Choudary praised attacks like the murder of British soldier Lee Rigby in 2013, justifying such violence as part of a broader struggle (Dodd, 2016).

Choudary’s ability to exploit free speech laws made him a significant threat. He radicalized countless individuals, including some who went on to commit acts of terrorism. While he was eventually jailed for supporting ISIS, his influence continues to be felt.

The Consequences of Britain’s Hospitality

The UK’s decision to offer refuge to Islamist leaders wasn’t made lightly, but the effects of those decisions are still being felt today. From domestic radicalization to international tensions, the legacy is a complex one.

Radicalization at Home

The presence of Islamist leaders created fertile ground for radicalization. Groups like al-Muhajiroun provided a pipeline for young Muslims to join extremist organizations. The 7/7 London bombings in 2005, carried out by British citizens, were a devastating reminder of the dangers posed by homegrown extremism. The attackers were influenced by ideologies promoted by figures like Bakri and Choudary.

Programs like Prevent, designed to tackle radicalization at its roots, have tried to address these issues. But they’ve faced criticism from all sides—some argue they stigmatize Muslim communities, while others say they don’t go far enough (Kundnani, 2014). Finding the right balance remains a challenge.

Strained Social Cohesion

The rhetoric of Islamist leaders has deepened divisions within British society. Their extremist views fueled mistrust between Muslim communities and the broader public. So-called Islamophobia surged in response to high-profile terror attacks, making many Muslims feel isolated and targeted. Within Muslim communities, moderate voices struggled to counteract the influence of radicals.

Geopolitical Repercussions

Hosting Islamist leaders also strained Britain’s relationships with allies in the Middle East. Countries like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan repeatedly criticized the UK for providing refuge to individuals they considered terrorists. These tensions made building trust in intelligence-sharing partnerships and complicated diplomatic efforts harder.

Steps Toward Change

The UK has taken significant steps to address these challenges in recent years. The Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 introduced measures to prevent individuals from promoting extremism, including banning organizations and restricting the movements of suspected terrorists. Community programs have also focused on engaging young Muslims and amplifying moderate voices to counter radical narratives.

But legislation alone isn’t enough. Tackling extremism requires a broader societal effort that fosters inclusion, promotes education, and ensures all communities feel valued and heard. By strengthening partnerships between government agencies, community leaders, and educators, Britain can build resilience against radicalization.

A Complicated Legacy

The UK’s decision to provide refuge to Islamist leaders was rooted in noble principles. It reflected a deep commitment to protecting the vulnerable and upholding human rights. Yet, these same principles were exploited by individuals who sought to undermine the freedoms that protected them.

As Britain grapples with these decisions' legacy, lessons must be learned. Striking a balance between upholding values and ensuring security isn’t easy, but it’s necessary. Britain can move toward a future where its ideals are a strength, not a vulnerability, by fostering dialogue, promoting inclusion, and investing in counter-radicalization efforts.

References

Casciani, D. (2014). Abu Qatada deported from UK to stand trial in Jordan. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com

Dodd, V. (2016). Anjem Choudary jailed for five and a half years for urging support of ISIS. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com

Kundnani, A. (2014). The Muslims are Coming! Islamophobia, Extremism, and the Domestic War on Terror. Verso Books.

Phillips, M. (2006). Londonistan: How Britain is creating a terror state within. Encounter Books.

Wiktorowicz, Q. (2005). Radical Islam Rising: Muslim Extremism in the West. Rowman & Littlefield.

Tim Orr is a scholar of Islam, Evangelical minister, conference speaker, and interfaith consultant with over 30 years of experience in cross-cultural ministry. He holds six degrees, including a master’s in Islamic studies from the Islamic College in London. Tim taught Religious Studies for 15 years at Indiana University Columbus and is now a Congregations and Polarization Project research associate at the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture at Indiana University Indianapolis. He has spoken at universities, including Oxford University, Imperial College London, the University of Tehran, Islamic College London, and mosques throughout the U.K. His research focuses on American Evangelicalism, Islamic antisemitism, and Islamic feminism, and he has published widely, including articles in Islamic peer-reviewed journals and three books.

Sign up for Dr. Tim Orr's Blog

Dr. Tim Orr isn't just your average academic—he's a passionate advocate for interreligious dialogue, a seasoned academic, and an ordained Evangelical minister with a unique vision.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.