Dr. Tim Orr

Racism remains one of the most persistent and painful issues in society. Amid cultural debates, Christians—especially white evangelicals—often find themselves divided on how to address it. Some emphasize personal repentance and reconciliation, while others stress the need for systemic change. But the gospel compels us to embrace both. We cannot be indifferent to racism simply because we object to secular frameworks like critical theory. Instead, we must engage the issue biblically, recognizing that sin infects individual hearts and the systems those individuals create. A Christian view acknowledges that sinful people create sinful systems. The problem with critical theory is that it relocates the problem of the human heart solely to structures, whereas the Bible teaches that both personal sin and unjust systems require redemption (Keller, 2021; Smith, 2019).

The Gospel and the Root of Racism

At its core, racism is a sin problem. The Bible teaches that all people are created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) and share equal worth in His sight. But sin distorts our view of one another. From the moment Adam and Eve sinned, alienation from God led to alienation from each other (Genesis 3). Racism is one manifestation of this brokenness—a form of pride that exalts one group over another, contrary to God's design (Volf, 1996).

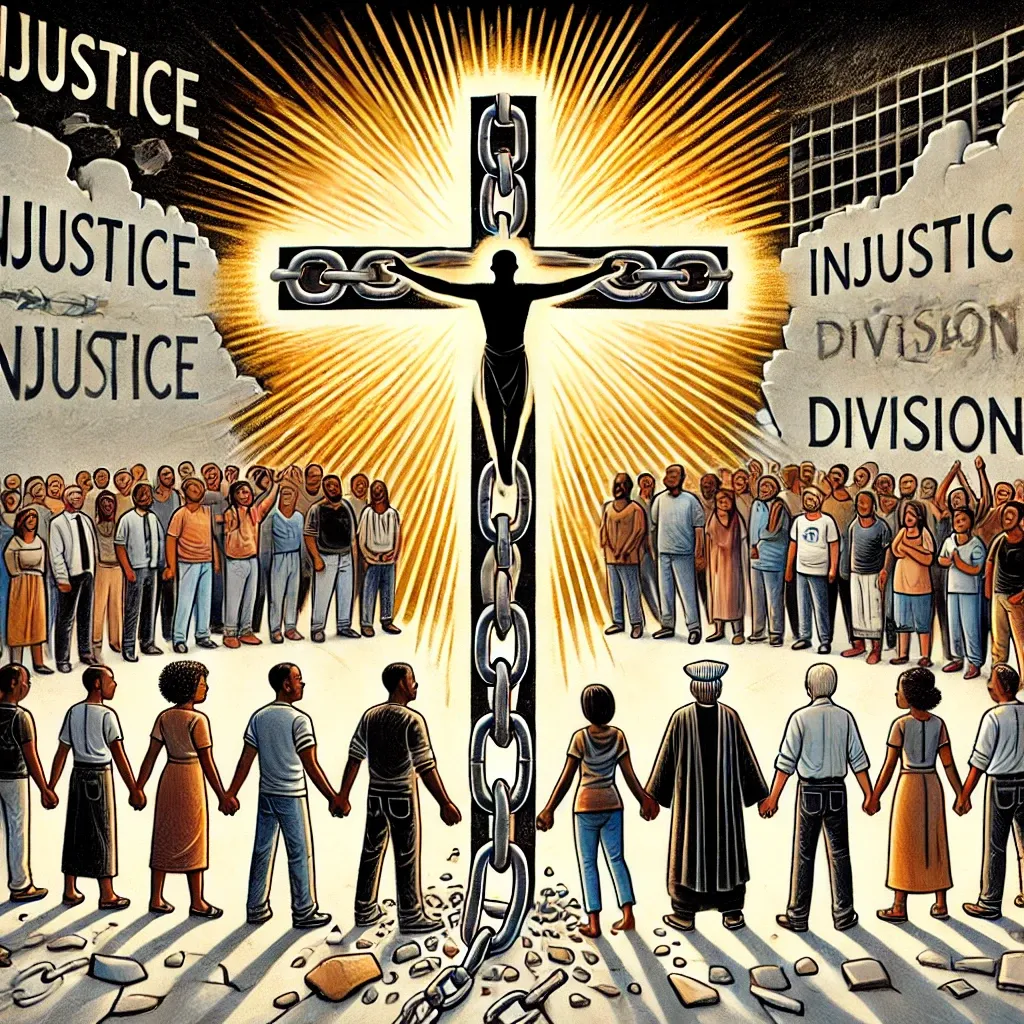

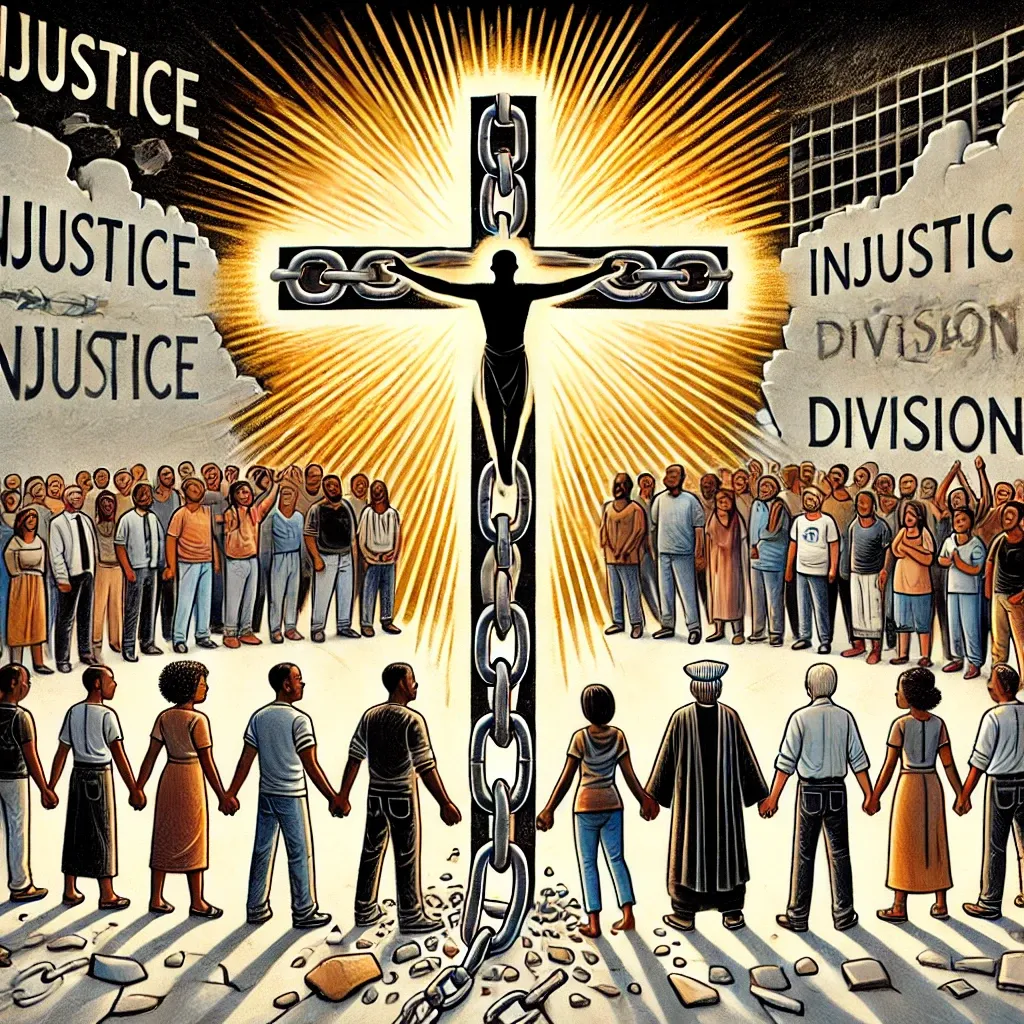

The gospel is not a superficial solution to racism; it is the only solution that gets to the root of the problem. Jesus Christ came to reconcile sinners to God and one another. Paul writes in Ephesians 2:14-16 that Christ has "broken down the dividing wall of hostility" between Jew and Gentile, creating "one new man in place of the two." The gospel does not erase cultural distinctiveness but demolishes the sinful barriers that divide us. It calls us to a unity rooted in Christ, not ideology, ethnicity, or political affiliation (Tisby, 2020).

Addressing Individual Sin: Repentance and Reconciliation

Since racism stems from sin, the first step in addressing it is repentance. This means that individuals must recognize and turn away from racist attitudes, prejudices, and actions. This is not just about avoiding overt racism but examining our hearts for hidden biases and how we may contribute to division. James 1:19 calls us to "be quick to listen, slow to speak, and slow to become angry." Repentance involves humility, listening, and being open to correction (Emerson & Smith, 2000).

But repentance is not enough on its own. True gospel repentance leads to reconciliation. Paul describes believers as "ministers of reconciliation" (2 Corinthians 5:18), tasked with healing the brokenness between people. This means intentionally building relationships across racial and cultural lines, seeking to understand rather than defend, and making amends where harm has been done. Jesus teaches that if someone has wronged another, they should seek to make it right before offering worship to God (Matthew 5:23-24). Reconciliation is a tangible expression of gospel transformation (Perkins, 2018).

Addressing Systemic Injustice: Biblical Justice and Social Structures

While personal repentance is vital, we cannot ignore the reality that sin also corrupts human institutions. Throughout Scripture, God calls His people to challenge injustice. The prophets rebuke Israel for institutionalized sin, commanding justice for the poor, the foreigner, and the marginalized (Isaiah 1:17, Amos 5:24, Micah 6:8). James warns against favoritism and economic injustice (James 2:1-9) (Kwon & Thompson, 2021).

Some evangelicals resist the idea of systemic injustice because it is often presented in the language of critical theory. However, rejecting critical theory does not mean rejecting the reality of structural sin. Scripture is clear that unjust systems exist because they are created and maintained by sinful people. The Old Testament law repeatedly addressed systemic oppression, and Jesus Himself condemned religious and political leaders who used their power unjustly (Matthew 23:23-24). The church must be willing to confront racial injustice in our society, not because we are beholden to secular ideology, but because we are beholden to the gospel (DeYoung & Gilbert, 2011).

The Church’s Role: A Community of Reconciliation

The church should model the reconciliation it preaches. This means intentionally creating multiethnic communities where people from different backgrounds worship, serve, and do life together as one body in Christ (Revelation 7:9). It means pastors and leaders must disciple their congregations in biblical justice, teaching that love for neighbor includes both personal relationships and social responsibility (Rah, 2009).

But it’s not just about diversity—it’s about transformation. Churches should ask hard questions: Do our church cultures reflect Christ’s vision of unity, or do they reflect the preferences of one dominant group? Are we genuinely engaging in cross-cultural friendships or just tolerating one another from a distance? Are we willing to challenge unjust policies that disproportionately harm specific communities, or do we remain silent out of fear of political controversy?

Practical engagement in racial justice is necessary. This might involve advocating for fair housing policies, supporting minority-led ministries, or mentoring young people in underserved communities. But these efforts must be rooted in the gospel. The church is not called to be just another activist group—it is called to be a prophetic voice that points to Christ, the only trustworthy source of justice and reconciliation (Lupton, 2015).

Conclusion: The Gospel Is the Answer

White evangelicals should not be indifferent to racism, even if they reject secular frameworks like critical theory. The gospel does not call us to choose between addressing personal racism and systemic injustice—it calls us to do both. Individual repentance and societal renewal are inseparable aspects of God’s redemptive work. The church can offer a unique and powerful witness in a divided world by embracing a gospel-centered approach.

Jesus did not come to modify our behavior but to transform our hearts. When hearts are truly transformed, societies are transformed, too. Through Christ, racial barriers can be broken, and true justice and reconciliation can be realized.

References

DeYoung, K., & Gilbert, G. (2011). What is the mission of the church? Crossway.

Emerson, M. O., & Smith, C. (2000). Divided by faith: Evangelical religion and the problem of race in America. Oxford University Press.

Keller, T. (2021). Hope in times of fear: The resurrection and the meaning of Easter. Viking.

Kwon, D., & Thompson, G. (2021). Redistributing power: The pursuit of racial justice in the church. Brazos Press.

Lupton, R. D. (2015). Charity detox: What charity would look like if we cared about results. HarperOne.

Perkins, J. (2018). One blood: Parting words to the church on race and love. Moody Publishers.

Rah, S. C. (2009). The next evangelicalism: Freeing the church from Western cultural captivity. IVP Books.

Smith, C. (2019). Religion: What it is, how it works, and why it matters. Princeton University Press.

Tisby, J. (2020). The color of compromise: The truth about the American church’s complicity in racism. Zondervan.

Volf, M. (1996). Exclusion and embrace: A theological exploration of identity, otherness, and reconciliation. Abingdon Press.

Tim Orr is a scholar of Islam, Evangelical minister, conference speaker, and interfaith consultant with over 30 years of experience in cross-cultural ministry. He holds six degrees, including a master’s in Islamic studies from the Islamic College in London. Tim taught Religious Studies for 15 years at Indiana University Columbus and is now a Congregations and Polarization Project research associate at the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture at Indiana University Indianapolis. He has spoken at universities, including Oxford University, Imperial College London, the University of Tehran, Islamic College London, and mosques throughout the U.K. His research focuses on American Evangelicalism, Islamic antisemitism, and Islamic feminism, and he has published widely, including articles in Islamic peer-reviewed journals and three books.